Fans of the board game Monopoly know that, if you land in jail, it’ll cost you $50 to get out. But it may surprise you to learn that real inmates in Michigan jails may also owe that much – and a lot more. County jails in our state are allowed to bill inmates nightly, and many do. But few recoup their costs by doing so, because criminal defendants are frequently indigent. While incarceration is an expensive prospect and inmates aren’t the most sympathetic of people, it’s unfair and unsustainable for counties to expect them to fund jails. Still, if it must be done, we should enact policies that reduce jail populations and give inmates better options for paying their debts.

There are two broad categories of crimes: felonies and misdemeanors. Felonies are serious crimes, and being convicted of one could result in large fines, incarceration of at least one year, or both. Misdemeanors, by contrast, are more minor crimes that carry lighter penalties. People convicted of a misdemeanor who serve time generally go to county jail rather than a state prison — specifically, the jail in the county where they committed their crime.

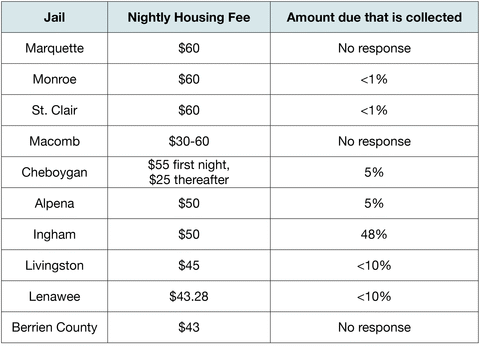

But would-be criminals should take note: Some Michigan counties take the concept of an offender’s “debt to society” more seriously (and literally) than others, and inmates in their jails may be released with massive debts. Here are the 10 most expensive places in Michigan to spend the night in jail:

Source: Mackinac Center FOIA requests to each county jail.

Each county bears the cost of housing inmates in its local jail. The Michigan Constitution requires each county to elect a sheriff, who is responsible for operating the jail. State law authorizes counties to charge jail inmates a $12 booking fee and up to $60 per night for the cost of their housing.

We surveyed the counties to find out how much their jails charge inmates, and found a wide range in housing fees. At least 68 jails impose some kind of fee. A few jails charge the full $60 authorized by statute, while a few, including Kalamazoo, Mason, Mecosta, Ogema, and Washtenaw, charge none at all.

One thing that all counties seem to have in common is difficulty collecting housing fees. Although we were not able to secure precise figures on how much jails are able to recoup, it appears that almost none of them collect even half of what they charge. Many reported collecting fewer than 10 percent of their housing fees, and for some, it was less than 1 percent. Jail administrators responded to our question about what portion of inmates pay their bill with answers like “unknown, but low,” “very low,” and “very, very low – maybe 2 in 450 [inmates pay].” One jail administrator told us, “It’s like getting blood from a turnip.” These responses reflect the fact that criminal offenders are more likely to be poor, which makes it unlikely they will fund county treasuries.

For instance, the person who is convicted of a misdemeanor and serves a standard 93-day sentence in a jail with a $60 nightly housing fee will end up owing the county more than $5,500. That doesn’t include penal fines, court costs, booking fees, victim restitution, attorneys’ fees, the cost of phone calls home and any purchases made from the jail commissary. One Michigan man ended up owing nearly $13,000 at the end of his case and sentence.

Some people think that inmate housing fees are equivalent to “user fees,” because they let us pass our criminal justice costs along to the people who made us incur them in the first place. That’s a logical stance, but it might not make good policy.

First, who benefits from incarcerating criminals? Society. Incapacitating them by locking them up is meant to bolster public safety. Courts make many criminals pay fines as punishment or as restitution to make their victims whole, and, once they have made these payments and served time behind bars, we say rightfully that they have “paid their debt to society.” But generally, the legal and judicial system is appropriately funded with tax dollars because it is a critical component of a just society.

Second, the user-fee model of financing jails is obviously failing. Very few jurisdictions in Michigan manage to collect even half their costs from their (involuntary) users, making the model simply a bad business practice. Moreover, it’s counterproductive. This kind of debt can pose an insurmountable barrier to successful reintegration in the community, especially because it’s visible in background checks conducted by prospective employers and universities. Holding people back from their full potential or forcing them out of the workforce entirely benefits no one and may contribute to additional criminality.

Fortunately, there are steps that counties can take to reduce their jail expenditures and recoup more of their money.

First, counties should ask their courts to release more criminal defendants on bail. Gov. Rick Snyder has noted that up to 60 percent of jail inmates statewide are incarcerated not because they’ve been convicted of a crime, but because they cannot afford to pay bail. Several other states are considering changes to or have changed their bail system from one based on a defendant’s ability to pay to one based on whether that defendant poses a risk to public safety. Legislation to enact bail reform is under discussion in Michigan, but at least one court in our state has already gone ahead and piloted a program to give all misdemeanor defendants bail. This could substantially cut down on jail expenditures without posing a risk to public safety.

Second, courts should provide indigent defendants with an attorney at the early stages in their trial. When this was tested in Michigan, it cut down on the average length of jail stay by nearly 30 percent in one county, and reduced overall jail use as well. (And it goes without saying that this policy is fairer for individual defendants.)

Finally, counties that cannot afford to do without passing some of their costs along to offenders should at least provide the option to sign up for a payment plan, or allow indigent defendants to do community service rather than try to come up with cash they don’t have.

Even the best policy proposals can’t work without proper funding, something both courts and the state will have to grapple with. Legal system funding issues need urgent attention, and adherence to the status quo is simply not an option.

Thanks to Jarrett Skorup and Chase Slaskinski for their contributions to this article.

|

Neither Inmates Nor Counties Get Out of Jail Free

Michigan counties try, unsuccessfully, to pass their jail expenditures on to inmates

Fans of the board game Monopoly know that, if you land in jail, it’ll cost you $50 to get out. But it may surprise you to learn that real inmates in Michigan jails may also owe that much – and a lot more. County jails in our state are allowed to bill inmates nightly, and many do. But few recoup their costs by doing so, because criminal defendants are frequently indigent. While incarceration is an expensive prospect and inmates aren’t the most sympathetic of people, it’s unfair and unsustainable for counties to expect them to fund jails. Still, if it must be done, we should enact policies that reduce jail populations and give inmates better options for paying their debts.

There are two broad categories of crimes: felonies and misdemeanors. Felonies are serious crimes, and being convicted of one could result in large fines, incarceration of at least one year, or both. Misdemeanors, by contrast, are more minor crimes that carry lighter penalties. People convicted of a misdemeanor who serve time generally go to county jail rather than a state prison — specifically, the jail in the county where they committed their crime.

But would-be criminals should take note: Some Michigan counties take the concept of an offender’s “debt to society” more seriously (and literally) than others, and inmates in their jails may be released with massive debts. Here are the 10 most expensive places in Michigan to spend the night in jail:

Source: Mackinac Center FOIA requests to each county jail.

Each county bears the cost of housing inmates in its local jail. The Michigan Constitution requires each county to elect a sheriff, who is responsible for operating the jail. State law authorizes counties to charge jail inmates a $12 booking fee and up to $60 per night for the cost of their housing.

We surveyed the counties to find out how much their jails charge inmates, and found a wide range in housing fees. At least 68 jails impose some kind of fee. A few jails charge the full $60 authorized by statute, while a few, including Kalamazoo, Mason, Mecosta, Ogema, and Washtenaw, charge none at all.

One thing that all counties seem to have in common is difficulty collecting housing fees. Although we were not able to secure precise figures on how much jails are able to recoup, it appears that almost none of them collect even half of what they charge. Many reported collecting fewer than 10 percent of their housing fees, and for some, it was less than 1 percent. Jail administrators responded to our question about what portion of inmates pay their bill with answers like “unknown, but low,” “very low,” and “very, very low – maybe 2 in 450 [inmates pay].” One jail administrator told us, “It’s like getting blood from a turnip.” These responses reflect the fact that criminal offenders are more likely to be poor, which makes it unlikely they will fund county treasuries.

For instance, the person who is convicted of a misdemeanor and serves a standard 93-day sentence in a jail with a $60 nightly housing fee will end up owing the county more than $5,500. That doesn’t include penal fines, court costs, booking fees, victim restitution, attorneys’ fees, the cost of phone calls home and any purchases made from the jail commissary. One Michigan man ended up owing nearly $13,000 at the end of his case and sentence.

Some people think that inmate housing fees are equivalent to “user fees,” because they let us pass our criminal justice costs along to the people who made us incur them in the first place. That’s a logical stance, but it might not make good policy.

First, who benefits from incarcerating criminals? Society. Incapacitating them by locking them up is meant to bolster public safety. Courts make many criminals pay fines as punishment or as restitution to make their victims whole, and, once they have made these payments and served time behind bars, we say rightfully that they have “paid their debt to society.” But generally, the legal and judicial system is appropriately funded with tax dollars because it is a critical component of a just society.

Second, the user-fee model of financing jails is obviously failing. Very few jurisdictions in Michigan manage to collect even half their costs from their (involuntary) users, making the model simply a bad business practice. Moreover, it’s counterproductive. This kind of debt can pose an insurmountable barrier to successful reintegration in the community, especially because it’s visible in background checks conducted by prospective employers and universities. Holding people back from their full potential or forcing them out of the workforce entirely benefits no one and may contribute to additional criminality.

Fortunately, there are steps that counties can take to reduce their jail expenditures and recoup more of their money.

First, counties should ask their courts to release more criminal defendants on bail. Gov. Rick Snyder has noted that up to 60 percent of jail inmates statewide are incarcerated not because they’ve been convicted of a crime, but because they cannot afford to pay bail. Several other states are considering changes to or have changed their bail system from one based on a defendant’s ability to pay to one based on whether that defendant poses a risk to public safety. Legislation to enact bail reform is under discussion in Michigan, but at least one court in our state has already gone ahead and piloted a program to give all misdemeanor defendants bail. This could substantially cut down on jail expenditures without posing a risk to public safety.

Second, courts should provide indigent defendants with an attorney at the early stages in their trial. When this was tested in Michigan, it cut down on the average length of jail stay by nearly 30 percent in one county, and reduced overall jail use as well. (And it goes without saying that this policy is fairer for individual defendants.)

Finally, counties that cannot afford to do without passing some of their costs along to offenders should at least provide the option to sign up for a payment plan, or allow indigent defendants to do community service rather than try to come up with cash they don’t have.

Even the best policy proposals can’t work without proper funding, something both courts and the state will have to grapple with. Legal system funding issues need urgent attention, and adherence to the status quo is simply not an option.

Thanks to Jarrett Skorup and Chase Slaskinski for their contributions to this article.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

More From CapCon