Little Evidence That Unions Make Workers Safer

Workplace injuries are plummeting in right-to-work states

Are workers safer when they’re forced to pay union fees in order to have a job?

Repeating a talking point used in Michigan and other states, union leaders at the AFL-CIO are warning West Virginians a right-to-work law would lead to more injuries and deaths on the job.

Right-to-work prevents unions from having workers fired for refusing to pay union fees. Right-to-work doesn’t restrict union membership or negotiations over safety equipment, training, or anything else.

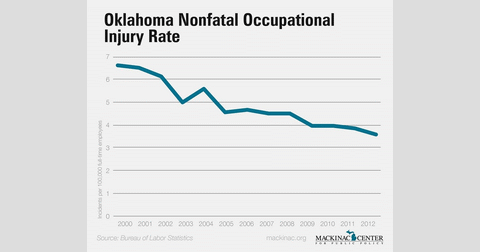

Recent federal data show workplace injury and fatality rates continuing a decades-long decline in right-to-work and forced unionization states alike. The latest U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics nonfatal work injury figures are from 2014, just one year after Michigan implemented right-to-work and two years after Indiana did so.

Michigan’s nonfatal occupational injury rate was 4.1 per 100,000 full-time employees in 2012, the year before right-to-work took effect. The state’s nonfatal work injury rate declined to 3.8 in 2013 and 3.7 in 2014.

In 2011 – the year before Indiana’s right-to-work law took effect – Indiana had a nonfatal work injury rate of 4.3 per 100,000 full-time employees. That rate dropped to 4.0 in 2012, dropped again to 3.8 in 2013, and was 4.0 in 2014.

Not only have new right-to-work states reported declining workplace injury rates, in many cases right-to-work states are statistically safer than forced unionization states.

West Virginia had a fatal work injury rate of 8.6 per 100,000 in 2013, higher than all but two right-to-work states. Does that mean mandatory union dues made West Virginia a more dangerous place to work than 22 right-to-work states?

Of course, the mining industry is central to West Virginia’s economy, and mining jobs are more dangerous than white collar positions.

This is a point the AFL-CIO hopes policymakers in states considering right-to-work will overlook in the face of “right-to-work is wrong” chants: the mix of industries in each state dramatically affects workplace injury rates, and the most dangerous jobs tend to be more prevalent in right-to-work states for geographic and other reasons.

Right-to-work states North Dakota and Wyoming had the highest fatal occupational injury rates in 2013, followed by forced unionization states West Virginia, Alaska, and New Mexico.

As of 2014, roughly 1 in 5 of the jobs in North Dakota and Wyoming was in a “Construction and Extraction Occupation” or a “Transportation and Material Moving Occupation” according to BLS. Fatal work injuries are far more common in construction, transportation, agriculture, and natural resource extraction jobs than in other professions.

In Hawaii – the state with the lowest fatal workplace injury rate in 2013 – “Construction and Extraction Occupations” and “Transportation and Material Moving Occupations” account for barely 1 in 10 jobs.

Union attempts to prove a causal relationship between right-to-work laws and more dangerous workplaces clash with BLS data nationally, too.

In recent years, the nation’s fatal workplace injury rate has declined while at the same time a growing percentage of American jobs are in right-to-work states.

In December 2006, 39 percent of America’s nonfarm employment was located in right-to-work states and the fatal work injury rate was 4.2 per 100,000 full-time workers.

By December 2014, 45 percent of America’s nonfarm jobs were in right-to-work states and the fatal work injury rate had dropped to 3.3.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.