The Most Bizarre Licenses in Michigan

Potato dealers, foresters, butter graders and more

In 43 states and Washington, D.C., a young person who has a dream of being a forester faces a fairly straightforward process: Get the necessary training and apply for a job. But to be a registered forester in Michigan, it's not so easy.

The state’s occupational code mandates fees and has a higher education requirement. It also places limits on someone with a criminal background. The process includes years of training for an associate or bachelor’s degree, followed by two years of working for someone else and payment of $90 in fees. The law also has a “good moral character” provision, meaning a person’s criminal background can be a barrier to work. (Unlike other state licenses, these requirements only apply to people who refer to themselves as a "registered forester.")

Those obstacles can be overwhelming for many people, and experts say the growth of such protectionist licensure regimes into so many professions has led to fewer opportunities for young people. It some cases, it can even lead to more crime. Research from Stephen Slivinski of Arizona State University links occupational regulations with higher criminal activity.

“Decades of academic literature indicate that gainful employment is one of the best ways to keep ex-prisoners from re-offending and ending up back in prison,” Slivinski said. “So, not surprisingly, occupational licensing barriers that make it harder or impossible for them to reintegrate into the labor force can increase the growth rate in criminal recidivism. In the states that have both high occupational licensing barriers and punitive ‘good character’ provisions, you see a significant increase in the growth rate of re-offenses within three years — an average of over 9 percent growth in the new-crime re-offense rate, which is over three-and-a-half times the national average for the ten-year period studied.”

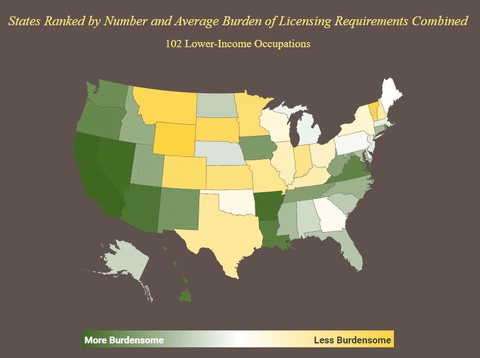

A new report from the Institute for Justice, a national public interest law firm, analyzes occupational licenses across the 50 states. “License to Work” ranks the states based on how restrictive they are when requiring a government permission slip for people to enter an industry. Today, more than 20 percent of Michigan workers are required to have a license.

According to IJ, Michigan is near the middle of the pack for licensing at number 30 (with one being the most restrictive and 50 being the least). But that’s a heavier burden than the rest of the Midwest. Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Kentucky all have lower licensing restrictions than Michigan. The IJ review focused on lower-income occupations.

“Occupational licensing limits competition, leading to higher prices and reduced access to jobs,” said Christina Walsh, director of activism and coalitions at IJ. “Reform is desperately needed, and is now being championed by a growing chorus of policymakers and scholars across the political spectrum.”

The state of Michigan requires licenses for hundreds of businesses and occupations. More than 20 percent of workers – one out of every five – must get special government permission in order to hold a job. That’s up from about 5 percent back in the 1950s, and most of the expansion in licensing is for middle- and low-income workers.

Some occupations are licensed in every state and have been for decades. For example, all 50 states license doctors, dentists, barbers, architects, nurses, optometrists, pharmacists and social workers.

But according to a national database of state licensing laws put together by the Goldwater Institute, there are many areas in which Michigan stands nearly alone in requiring a government license to work.

- Airport manager: There are no mandatory training hours, but the state requires an examination. No other state has this requirement.

- Animal control officer: Michigan requires 100 hours of training, more than any other state. It also considers a person’s criminal background and is one of only seven that require any license.

- Potato dealer: The state requires no hours, but state law mandates a $100 fee. Only two states have a similar law.

- Forester: Michigan’s forester regulation covers only 226 people and the law “lacks a clear scope of practice,” according to a report from the Office of Regulatory Reinvention. It appears that very few states license foresters and very few complaints about them could be found.

- Court reporter: The state mandates a high school degree, a training workshop, a passing score on a test and a $65 fee. Only 13 states have this type of license.

- Painter: If you want to be an auto mechanic in Michigan, the state requires $25 in fees and a repair test. But if you want to earn a living repainting old barns, the state forces you to pay $295 in fees, pass a test, and take 60 hours of prelicensure courses. A person also has to be 18 years of age. The number of states requiring a license has gone from 10 to 28 in the past few years, but none of Michigan’s neighboring states requires this license. House Bill 4608 has been introduced to delicense painters.

- Librarian: People employed by a library in Michigan need a GED or high school diploma and to complete a workshop. School librarians need at least four years of school and a teaching certificate.

- Plant grower: According to the state, a license is required to sell biennials, small fruit plants, asparagus or rhubarb roots. There are no mandated educational hours, but the state of Michigan does mandate an inspection and more than $150 in fees. If you have a friend or neighbor over, you can serve them plants grown in your garden. But if you sell it without a license, you’re breaking state law.

- Butter grader: If you want to earn a living examining butter for flavor, aroma, body or other factors, Michigan requires that you take a test and go through training. Only three states mandate a license in this area.

- Roofer: You don’t need a license to lay shingles in Ohio, Indiana or Wisconsin. But Michigan joins a minority of states in requiring it. Would-be roofers need 60 hours of courses, must pay nearly $300 in fees and pass a test. Those with a criminal background face impediments.

- Property manager: People who oversee the leasing of property for others must have a real estate sales or brokerage license. If a person wants to be a landlord – renting out their own property – there is no licensing, but if you hire someone to oversee your rental property, the state requires three years of experience, 90 hours of training, an exam, and hundreds of dollars in fees. A person’s criminal record can also get them denied the ability to work, in an area licensed by only four states.

- Siding and gutters: It’s easy to see if someone hung siding or gutters correctly, and most other states get by without mandating licensing. Michigan, though, requires hundreds of dollars in fees, 60 hours of courses, an exam, and “good moral character” of applicants.

- Landscape architect: From its founding until 2009, the state of Michigan survived without requiring landscape architects to hold a license. It is a “titling license,” meaning it provides specific protection to just the few people with that title in the state. The Office of Regulatory Reinvention reports that “The title protection that comes from the license of landscape architects does not provide a public health and safety benefit sufficient to warrant use of public resources to regulate them.” A proposed law, House Bill 4693, would repeal this license.

- Floor sander: If a Michigander wants to lay carpet or hang drywall, no license is needed. But finishing contractors – including those engaged in scraping and sanding – are forced to be licensed. Michigan is one of only nine states to require this license.

Experts say that licensing has a variety of negative effects. Research has found that it drives up costs for consumers, leads to job loss, exacerbates income inequality, and makes it more likely that ex-convicts return to prison (since it is harder for them to find work). Morris Kleiner of the University of Minnesota has said that in Michigan, licensing rules cost 125,000 jobs and $2,700 per family annually.

Rep. Brandt Iden, a Republican from Oshtemo Township, is the chair of the House Regulatory Reform Committee. His committee has passed several bills that roll back occupational regulations, and he is looking to do more in a comprehensive manner.

“The reality is there are a lot of unnecessary regulations surrounding certain licensure,” Iden said. “I believe it is incumbent upon the Legislature to take a hard look at what is necessary for citizen safety versus what is just burdensome and excess red tape. Therefore, in the coming year, I am committed to reviewing these regulations to try and find a solution which will help grow our economy for all Michigan citizens.”

Editor's Note: This article was updated to make clear that the forester license is an optional registration.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Mackinac Center calls on lawmakers to ease licensing barriers for people with criminal records

Mackinac Center calls on lawmakers to ease licensing barriers for people with criminal records

Athletic trainers call timeout on rising licensing costs

Athletic trainers call timeout on rising licensing costs

Michigan’s arbitrary process for banning license plates

Michigan’s arbitrary process for banning license plates

Jobs agency ghost-writes its own public relations