Second MEA President Used $200,000+ Union Salary to ‘Spike’ Public Pension

Special deal allows Iris Salters to collect $140,000 per year

The former head of Michigan's largest teachers union was able to spike her pension by basing it on a union executive salary rather than her past earnings as a teacher. This special deal means taxpayers are on the hook for part of the extra $100,000 in annual pension benefits.

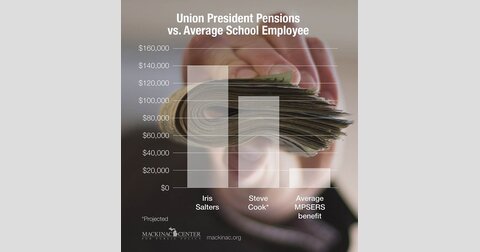

Former Michigan Education Association President Iris Salters draws an annual pension of $140,000 from the state of Michigan. That's in line with longtime educators who reached the top of their profession — from school district superintendents to community college presidents.

However, Salters didn’t get her six-figure government pension payout from reaching a top spot in public education, although she was a teacher in Kalamazoo for 32 years. Instead, when she left to become an official with the state's teachers union in 1999, she worked out a deal with the school district.

According to information obtained by Michigan Capitol Confidential and confirmed by the school district, Salters was considered an “educator on loan” to the MEA while employed as a high-level union executive. She eventually became president of the state’s largest teachers union, collecting a salary of $235,447 in her final year before retiring in 2011.

The special arrangement with the school district also allowed Salters to “count” her years as a highly paid union executive in the formula that produces her $140,000 annual payout from the underfunded school pension system. The school district made pension fund contributions on Salters' behalf for 12 years, with the cost reimbursed by the MEA. But the state is required to pay “catch up” payments caused by past pension underfunding.

The special deal allowed Salters to turn a modest teachers’ pension into that of a college president.

The top of the scale salary for a Kalamazoo Public Schools teacher was $75,160 in 2011. A Kalamazoo teacher who retired at that level after working 32 years would receive an annual pension of $36,077. That’s more than $100,000 less than Salters’ pension.

“Our attorney at the time, John Manske, and our current attorney, Marshall Grate, have both advised the district that the agreement regarding Iris Salters was, and remains, legal in accordance with Section 71 of the Public School Employees Retirement Act,” said Alex Lee, executive director of communications for Kalamazoo Public Schools, in an email.

Salters’ “educator on loan” deal is similar to the arrangement current MEA President Steve Cook has with the Lansing School District. Cook’s deal will allow him to earn a six-figure annual pension despite only earning a modest paraprofessional salary for 15 years with the school district. Because of liabilities in the pension system, state taxpayers are picking up some of this cost.

After Michigan Capitol Confidential discovered the special Cook deal and began investigating other top union officials, the MEA has told other media outlets that it has made several “educator on loan” deals over the years. The MEA did not respond to a request for comment.

The arrangements of Cook and Salters are legal under the Public School Employees Retirement Act of 1979. School employees who went on a “professional services leave” before Oct. 1, 1996 were allowed to use their time on the job with a professional service organization to earn more “service credits” with the school retirement system. Those employees were also allowed to use their salary with the private employer as the basis on which their school pension benefits are calculated.

The state Office of Retirement Services said between two and 14 individuals are eligible for deals similar to the ones used by Cook and Salters. However, the state also said the deadline for such a deal was October 1, 1996. The Kalamazoo school district said Salters left its employment for the MEA in 1999, three years after the deadline.

Caleb Buhs, spokesman for the state of Michigan, said Salters was eligible for the special deal because she first took leave and started with the local teachers union, the Kalamazoo Education Association, in 1992, or four years before the deadline.

Tom Watkins, who served as the state superintendent of public education from 2001-2004, said he wasn’t in agreement with “educator on loan” applying to private union officials who left public education positions.

“If you left, you left,” Watkins said. “That’s how I look at it.”

Watkins said these types of arrangements should not be a surprise to the public.

“If these are the rules, and people find it unacceptable, they need to change the rules,” Watkins said. “We need to have clear rules — transparency in government. People should know about it.”

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

State teachers union loses members, revenue

State teachers union loses members, revenue

Teachers union distorts record on education spending

Teachers union distorts record on education spending

Michigan Education Association’s power is on a long decline

Michigan Education Association’s power is on a long decline