Commentary

A Steady Decline for Unions Under Michigan’s Right-to-Work Law

The birthplace of the modern labor movement finds workers increasingly opting out

Mackinac Center for Public Policy

In the years since Michigan became a right-to-work state — where workers can choose whether to belong and pay dues to a union — organized labor has seen its power diminished as members have increasingly resigned their membership.

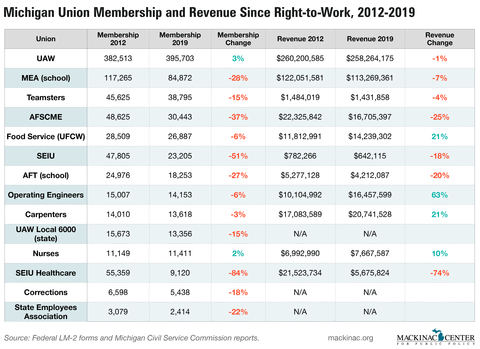

Since 2012, the year before right-to-work went into effect, the 14 major public and private sector unions in Michigan have seen a combined loss of nearly 130,000 members. This is a 16 percent drop overall. These large unions in Michigan reported at least $20 million less in revenue in 2019 then they did in 2012. The drop has helped drive Michigan, the birthplace of the modern labor movement, from having the fifth highest unionization rate in the United States to being nearly out of the top 10 — a once unthinkable proposition.

In 2012, amid union protests that at times turned violent, and a contentious legislative battle that included threats to policymakers, Michigan allowed workers a choice in union membership. In the seven years since, the state has had robust job growth — both in the public and private sector — while union membership steadily fell.

According to federal Labor Department data, since 2013, Michigan has added nearly 400,000 private sector jobs, for a gain of 11 percent. The number of jobs in the public sector grew by 4,100, too. This job growth suggests that the decline in union membership is a result of workers saying “no thanks” to unions who purport to serve their best interests, rather than a consequence of a shrinking economy.

This steady decline in membership has financial ramifications for unions, namely, a loss of revenue. It means unions have fewer dollars available to spend on politics and electioneering. After Democrats swept the elections for statewide offices in November 2018, The Atlantic diagnosed the winning strategy and noted this about organized labor:

“Not everyone delivered [during the midterms]. Officials in the state party were surprised, for example, to see several of the unions falling short of their promises, their leaders apparently themselves not realizing just how much the state’s right-to-work law had cut their ranks.”

Here are the membership and revenue numbers for Michigan’s largest unions since it became a right-to-work state.

The United Auto Workers has seen a slight membership increase since 2012. But this may not be all good news for the union. Membership may be up, but considering that there has been substantial growth in the auto sector since then, one might reasonably expect UAW membership to be even higher.

Further, membership in the UAW increased every year since 2009, but it then fell for the first time in a decade last year. The most recent federal filing shows a 10 percent drop in membership just from 2017 to 2018. That was perhaps driven by recent corruption charges against top union officials and unflattering news headlines about the hypocrisy of using nonunion labor to build a vacation home for the UAW’s recently retired president. And membership is down almost 45 percent since 2001.

Officials at the Michigan Education Association predicted they would lose few members as a result of right-to-work, saying that school employees highly value the work the MEA does. But the reality is that 32,000 teachers and other school employees have opted out of buying what the MEA is selling, resulting in a drop of 28 percent. The American Federation of Teachers of Michigan, a smaller teachers union, lost nearly 7,000 members, or 27 percent.

Other government unions are also faring poorly. Michigan AFSCME affiliates, which represent mostly local public employees, lost 18,000 members, or 37 percent, since 2012. The largest unions representing state employees are also down: the Michigan State Employees Association, by 22 percent; UAW Local 6000, by 15 percent and the union for corrections officers by 18 percent.

And despite the noted job gains in the private sector, unions there aren’t seeing growth in Michigan. The state Teamsters union branches have lost a net 7,000 members, which is a 15 percent drop. Food service workers in the Food and Commercial Workers union are down 6 percent. The Service Employees International Union branches have had a multitude of issues and seen membership cut in half, a loss of nearly 25,000 members. Even operating engineers and carpenters unions are down despite huge increases in the road building and construction industries. Only nurses unions have increased membership, but by only 2 percent in a booming health care space.

Some unions in the Great Lake State appear to be in a downward spiral. Infighting and corruption has meant at least two major unions — the Detroit Federation of Teachers and Michigan’s oldest state employee union, the Michigan State Employees Association — have both been placed under the control of outside trustees. And the end of a dues scheme by which tens of thousands of home caregivers were forcibly unionized by the SEIU Healthcare has meant an astounding 84 percent membership loss.

In June 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that all public sector workers have a choice in belonging to or paying dues and fees to a union. It is too early to determine if other states with large numbers of union members will follow Michigan’s experience in the right-to-work era, but Michigan’s results point to one possible future.

|

A Steady Decline for Unions Under Michigan’s Right-to-Work Law

The birthplace of the modern labor movement finds workers increasingly opting out

In the years since Michigan became a right-to-work state — where workers can choose whether to belong and pay dues to a union — organized labor has seen its power diminished as members have increasingly resigned their membership.

Since 2012, the year before right-to-work went into effect, the 14 major public and private sector unions in Michigan have seen a combined loss of nearly 130,000 members. This is a 16 percent drop overall. These large unions in Michigan reported at least $20 million less in revenue in 2019 then they did in 2012. The drop has helped drive Michigan, the birthplace of the modern labor movement, from having the fifth highest unionization rate in the United States to being nearly out of the top 10 — a once unthinkable proposition.

In 2012, amid union protests that at times turned violent, and a contentious legislative battle that included threats to policymakers, Michigan allowed workers a choice in union membership. In the seven years since, the state has had robust job growth — both in the public and private sector — while union membership steadily fell.

According to federal Labor Department data, since 2013, Michigan has added nearly 400,000 private sector jobs, for a gain of 11 percent. The number of jobs in the public sector grew by 4,100, too. This job growth suggests that the decline in union membership is a result of workers saying “no thanks” to unions who purport to serve their best interests, rather than a consequence of a shrinking economy.

This steady decline in membership has financial ramifications for unions, namely, a loss of revenue. It means unions have fewer dollars available to spend on politics and electioneering. After Democrats swept the elections for statewide offices in November 2018, The Atlantic diagnosed the winning strategy and noted this about organized labor:

“Not everyone delivered [during the midterms]. Officials in the state party were surprised, for example, to see several of the unions falling short of their promises, their leaders apparently themselves not realizing just how much the state’s right-to-work law had cut their ranks.”

Here are the membership and revenue numbers for Michigan’s largest unions since it became a right-to-work state.

The United Auto Workers has seen a slight membership increase since 2012. But this may not be all good news for the union. Membership may be up, but considering that there has been substantial growth in the auto sector since then, one might reasonably expect UAW membership to be even higher.

Further, membership in the UAW increased every year since 2009, but it then fell for the first time in a decade last year. The most recent federal filing shows a 10 percent drop in membership just from 2017 to 2018. That was perhaps driven by recent corruption charges against top union officials and unflattering news headlines about the hypocrisy of using nonunion labor to build a vacation home for the UAW’s recently retired president. And membership is down almost 45 percent since 2001.

Officials at the Michigan Education Association predicted they would lose few members as a result of right-to-work, saying that school employees highly value the work the MEA does. But the reality is that 32,000 teachers and other school employees have opted out of buying what the MEA is selling, resulting in a drop of 28 percent. The American Federation of Teachers of Michigan, a smaller teachers union, lost nearly 7,000 members, or 27 percent.

Other government unions are also faring poorly. Michigan AFSCME affiliates, which represent mostly local public employees, lost 18,000 members, or 37 percent, since 2012. The largest unions representing state employees are also down: the Michigan State Employees Association, by 22 percent; UAW Local 6000, by 15 percent and the union for corrections officers by 18 percent.

And despite the noted job gains in the private sector, unions there aren’t seeing growth in Michigan. The state Teamsters union branches have lost a net 7,000 members, which is a 15 percent drop. Food service workers in the Food and Commercial Workers union are down 6 percent. The Service Employees International Union branches have had a multitude of issues and seen membership cut in half, a loss of nearly 25,000 members. Even operating engineers and carpenters unions are down despite huge increases in the road building and construction industries. Only nurses unions have increased membership, but by only 2 percent in a booming health care space.

Some unions in the Great Lake State appear to be in a downward spiral. Infighting and corruption has meant at least two major unions — the Detroit Federation of Teachers and Michigan’s oldest state employee union, the Michigan State Employees Association — have both been placed under the control of outside trustees. And the end of a dues scheme by which tens of thousands of home caregivers were forcibly unionized by the SEIU Healthcare has meant an astounding 84 percent membership loss.

In June 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that all public sector workers have a choice in belonging to or paying dues and fees to a union. It is too early to determine if other states with large numbers of union members will follow Michigan’s experience in the right-to-work era, but Michigan’s results point to one possible future.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

More From CapCon