Commentary

There Is No Relationship Between College Graduates and Economic Growth

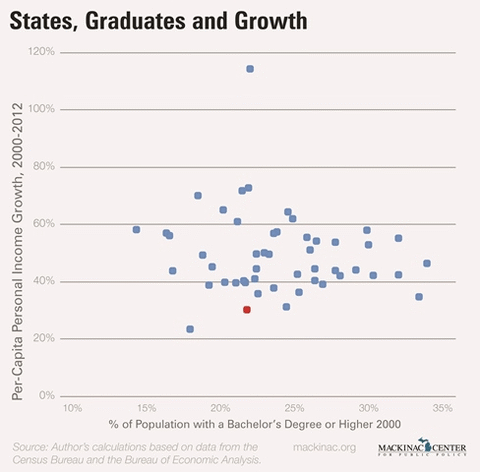

It often is argued that the key to grow a state's economy is to increase the population of college graduates.

Yet, over the last decade, this factor has proved to be a poor predictor of economic growth. The states that have a relatively high concentration of college graduates do not expand at rates statistically different from states that do not.

The following chart shows the percentage of each state's adult population with a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2000, and the state's per capita personal income growth from 2000 through 2012 (Michigan is the red dot).

If there were a firm connection between the two, you'd see a clumping of points sloping upward. Clearly, this is not the case.

Still, it's often observed that states with high incomes are those with a high proportion of college grads. But this observation does not tell us anything about how relatively poor states become richer, or, for that matter, how relatively rich states become poorer.

Take Colorado, for example. It was in the top 10 for both per capita personal income and in grads in 2000. It was still in the top 10 for grads in 2012, but had fallen to 16th in per capita personal income.

Michigan's proportion of college graduates didn't change much from 2000 to 2012, but it dropped from 18th highest in per capita personal income down to 36th.

Oregon increased its college population and still dropped nine places in the per capita personal income rankings.

There are states that fit the model that the talent mercantilists (people who assume more college graduates means there is more talent in the economy) are pushing. Vermont continues to have a high level of graduates, and it increased its per capita personal income from 29th to 21st from 2000 to 2012.

(For a look at the relationship between grads and growth using different years and lags, see my 2010 report.)

On an individual level, obtaining a college degree may still, on net, pay dividends for most people (although that may be changing as colleges continue to become more expensive). This, however, does not translate to the state level.

From that perspective, it's better to encourage growth by making it easier for individuals to produce, earn and keep the fruits of their labor — lowering taxes, limiting regulatory burdens and protecting property rights.

|

There Is No Relationship Between College Graduates and Economic Growth

It often is argued that the key to grow a state's economy is to increase the population of college graduates.

Yet, over the last decade, this factor has proved to be a poor predictor of economic growth. The states that have a relatively high concentration of college graduates do not expand at rates statistically different from states that do not.

The following chart shows the percentage of each state's adult population with a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2000, and the state's per capita personal income growth from 2000 through 2012 (Michigan is the red dot).

If there were a firm connection between the two, you'd see a clumping of points sloping upward. Clearly, this is not the case.

Still, it's often observed that states with high incomes are those with a high proportion of college grads. But this observation does not tell us anything about how relatively poor states become richer, or, for that matter, how relatively rich states become poorer.

Take Colorado, for example. It was in the top 10 for both per capita personal income and in grads in 2000. It was still in the top 10 for grads in 2012, but had fallen to 16th in per capita personal income.

Michigan's proportion of college graduates didn't change much from 2000 to 2012, but it dropped from 18th highest in per capita personal income down to 36th.

Oregon increased its college population and still dropped nine places in the per capita personal income rankings.

There are states that fit the model that the talent mercantilists (people who assume more college graduates means there is more talent in the economy) are pushing. Vermont continues to have a high level of graduates, and it increased its per capita personal income from 29th to 21st from 2000 to 2012.

(For a look at the relationship between grads and growth using different years and lags, see my 2010 report.)

On an individual level, obtaining a college degree may still, on net, pay dividends for most people (although that may be changing as colleges continue to become more expensive). This, however, does not translate to the state level.

From that perspective, it's better to encourage growth by making it easier for individuals to produce, earn and keep the fruits of their labor — lowering taxes, limiting regulatory burdens and protecting property rights.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

More From CapCon