Commentary

MSU Scholar Ignores School Revenue Sources

Says revenue has been cut

Michigan State University professor David Arsen recently appeared on public radio to discuss the findings of his new research into the causes of school district financial distress.

Arsen’s research lays most of the blame for growing deficits and shrinking fund balances at the feet of state policymakers. In an accompanying article he co-authored with two other education professors and an economist, he argues that these policies exacerbate the declining enrollment trend experienced widely across Michigan and “reinforce a fierce downward spiral,” particularly in high-minority urban districts.

Dozens of school districts have at one time been under close watch by the Michigan Department of Education because of their shaky fiscal foundations. Some districts that have come under emergency financial management, like Muskegon Heights and Highland Park, have experienced somewhat better fiscal outcomes than others, like Detroit Public Schools. Financial hardships led to the dissolution of Inkster and Buena Vista school districts in 2013.

In trying to explain the phenomenon, Arsen claimed, “Statewide, overall inflation-adjusted revenue per pupil has declined by about 25 percent since 2002,” he told Michigan Radio host Lester Graham.

However, the claim falls apart under the weight of closer scrutiny.

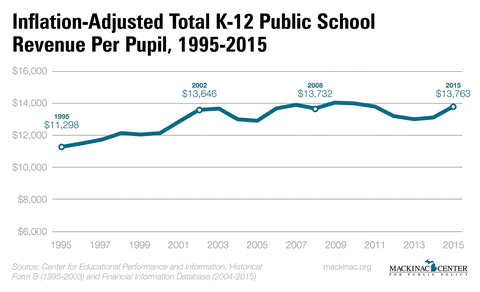

Arsen’s article includes a graph to reinforce the point that “statewide general fund revenue per-pupil has declined by roughly 25 percent since 2002.” The graph cites “Bulletin 140” (presumably Bulletin 1014) from the Michigan Department of Education as the source for the comparison with 2013, the most recent year of data used in the analysis.

Bulletin 1014 does not include significant chunks of K-12 funding that pay for non-general fund programs, such as those used for special education, nor does it include money used to purchase property or to finance school construction. As the Mackinac Center has pointed out before, Arsen’s data source also leaves out revenues collected by intermediate school districts — more than $2.6 billion in 2014-15.

A holistic view of Michigan K-12 education funding provides a less frightening picture. Adjusted for changing dollar values, the state’s public school coffers grew dramatically from 1995 to 2002. Since that time, figures have fluctuated modestly, resulting in a largely flat trend. In the following 13 years, real per pupil revenues grew by about 1 percent, a far cry from Arsen’s claim.

The omission of ISD revenues is particularly startling because those funds are predominantly used to provide center-based programs for special-needs students. Arsen and his colleagues identify inadequate state reimbursement of special education programs as a driving factor behind declining school district fund balances.

Another culprit Arsen points to is the method used to count students for the main funding formula. Districts count students for state aid payments based on a “90-10” weighted enrollment average — 90 percent of students from October of the current school year and 10 percent from the previous February. The balance has shifted several times over the years, at one point based on a 50-50 split.

Arsen and his colleagues say the current arrangement harms districts that are losing students; they specifically blame state policies that allow families to leave for public charter schools or other nearby districts. Getting 10 percent of funds based on last year’s students is not enough to cope with continuing financial obligations districts face, they argue. (Funny how seldom one hears the inverse argument made when enrollments are growing.)

The article presumes districts not only deserve greater protection as students leave for greener pastures, but also that they need the protection to stave off emergency financial measures. Recent evidence suggests the topic deserves a closer look.

Days after Arsen’s interview, The Detroit News reported that the number of Michigan school districts on the state’s financial watch list has decreased from 41 to 23. Less than one-third of the 23 districts are in measurably worse shape compared to the previous year.

These trends emerge even as Michigan’s annual public school enrollment continues to decline (although the decline has slowed a bit) and while the rate of students enrolling across district lines through Schools of Choice grows. And the 90-10 accounting rule for state funding continues.

The state could benefit from discussions about improving equity in the school funding formula and ensuring a greater share of dollars reach students where they choose to be served.

But let’s also not forget that just injecting more resources into public schools is unlikely to make much of a difference when it comes to boosting student achievement, as a recently published Mackinac Center study suggests. And let’s proceed with a fuller understanding of the financial picture, wary of policy prescriptions that avoid hard questions of how schools can adapt to serve students better.

|

MSU Scholar Ignores School Revenue Sources

Says revenue has been cut

Michigan State University professor David Arsen recently appeared on public radio to discuss the findings of his new research into the causes of school district financial distress.

Arsen’s research lays most of the blame for growing deficits and shrinking fund balances at the feet of state policymakers. In an accompanying article he co-authored with two other education professors and an economist, he argues that these policies exacerbate the declining enrollment trend experienced widely across Michigan and “reinforce a fierce downward spiral,” particularly in high-minority urban districts.

Dozens of school districts have at one time been under close watch by the Michigan Department of Education because of their shaky fiscal foundations. Some districts that have come under emergency financial management, like Muskegon Heights and Highland Park, have experienced somewhat better fiscal outcomes than others, like Detroit Public Schools. Financial hardships led to the dissolution of Inkster and Buena Vista school districts in 2013.

In trying to explain the phenomenon, Arsen claimed, “Statewide, overall inflation-adjusted revenue per pupil has declined by about 25 percent since 2002,” he told Michigan Radio host Lester Graham.

However, the claim falls apart under the weight of closer scrutiny.

Arsen’s article includes a graph to reinforce the point that “statewide general fund revenue per-pupil has declined by roughly 25 percent since 2002.” The graph cites “Bulletin 140” (presumably Bulletin 1014) from the Michigan Department of Education as the source for the comparison with 2013, the most recent year of data used in the analysis.

Bulletin 1014 does not include significant chunks of K-12 funding that pay for non-general fund programs, such as those used for special education, nor does it include money used to purchase property or to finance school construction. As the Mackinac Center has pointed out before, Arsen’s data source also leaves out revenues collected by intermediate school districts — more than $2.6 billion in 2014-15.

A holistic view of Michigan K-12 education funding provides a less frightening picture. Adjusted for changing dollar values, the state’s public school coffers grew dramatically from 1995 to 2002. Since that time, figures have fluctuated modestly, resulting in a largely flat trend. In the following 13 years, real per pupil revenues grew by about 1 percent, a far cry from Arsen’s claim.

The omission of ISD revenues is particularly startling because those funds are predominantly used to provide center-based programs for special-needs students. Arsen and his colleagues identify inadequate state reimbursement of special education programs as a driving factor behind declining school district fund balances.

Another culprit Arsen points to is the method used to count students for the main funding formula. Districts count students for state aid payments based on a “90-10” weighted enrollment average — 90 percent of students from October of the current school year and 10 percent from the previous February. The balance has shifted several times over the years, at one point based on a 50-50 split.

Arsen and his colleagues say the current arrangement harms districts that are losing students; they specifically blame state policies that allow families to leave for public charter schools or other nearby districts. Getting 10 percent of funds based on last year’s students is not enough to cope with continuing financial obligations districts face, they argue. (Funny how seldom one hears the inverse argument made when enrollments are growing.)

The article presumes districts not only deserve greater protection as students leave for greener pastures, but also that they need the protection to stave off emergency financial measures. Recent evidence suggests the topic deserves a closer look.

Days after Arsen’s interview, The Detroit News reported that the number of Michigan school districts on the state’s financial watch list has decreased from 41 to 23. Less than one-third of the 23 districts are in measurably worse shape compared to the previous year.

These trends emerge even as Michigan’s annual public school enrollment continues to decline (although the decline has slowed a bit) and while the rate of students enrolling across district lines through Schools of Choice grows. And the 90-10 accounting rule for state funding continues.

The state could benefit from discussions about improving equity in the school funding formula and ensuring a greater share of dollars reach students where they choose to be served.

But let’s also not forget that just injecting more resources into public schools is unlikely to make much of a difference when it comes to boosting student achievement, as a recently published Mackinac Center study suggests. And let’s proceed with a fuller understanding of the financial picture, wary of policy prescriptions that avoid hard questions of how schools can adapt to serve students better.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

More From CapCon