Last week, we highlighted problems with the Union Charter Township government, including a pervasive anti-growth attitude toward new developments. One family’s struggle with local leaders illustrates the extent of the township’s overreach.

The brothers William, Richard, Ronald and Robert Ervin own land in the township. These local developers have twice been kept from developing their property by local government. In two separate instances, the township effectively regulated away the value of property the Ervin brothers wanted to sell.

In 2023, the brothers wanted to divide their 40-acre parcel into two parts so they could sell one part to a younger relative. The township, however, refused to grant the requested land division. Employees claimed that the intended development (the construction of a home) was contrary to both the township’s zoning ordinance and its master plan.

Local governments frequently use zoning ordinances and master plans to manage and control development. A zoning ordinance restricts how a property can be used, while a master plan is a long-term guide.

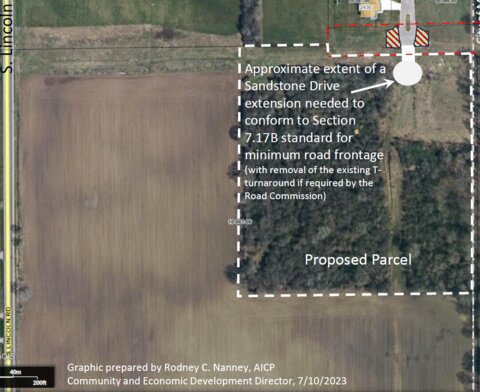

According to the Ervin brothers, the township would grant permission to divide the land, but only if their prospective buyer would build a road, ending with a cul-de-sac, on his property. Township employees also wanted the buyer to build out a public water line, at his expense, that could be tapped if future growth occurred on the remaining, adjacent 30–acre parcel.

According to the prospective buyer, extending the current road and adding the cul-de-sac would have cost approximately $100,000, a steep price for land valued at $60,000. Installing a water line that would serve future development by others would be an additional expense, far greater than the cost of getting a line to his own house.

Union Township officials denied the allegations.

“The Township Administration does not engage in foot-dragging or stifle or stymie land development,” the township told Michigan Capitol Confidential in an email. “The allegation of possible retribution is abhorrent and false. The Township Administration strives to ensure that all who interact with staff are treated with respect and with a focus on a successful outcome for any issue or challenge that needs resolution.”

Township employees also appear to be interested in having the Ervins build a quarter-mile road as part of the larger land division, according to a letter the township sent to William Ervin. The letter cited the township master plan, which included a street to Lincoln Road, a much larger thoroughfare.

The Ervins disagreed with the township’s decision to deny their request to divide the land, and they hired a lawyer to argue their case before the township’s Zoning Board of Appeals. The brothers won their appeal quickly, but they and their buyer chose not to proceed with the sale. Once again, the township was the issue.

The township’s master plan and its requirements made the development of the younger Ervin’s property untenable. Though the brothers won the land division they sought, they had no solution for the township’s demands for extending the public water line or building a road. For this and other reasons, the parties chose not to complete the sale.

Requiring property owners to build infrastructure for future public benefit is not the proper role of government. This is particularly true since a master plan is merely a guide for community development; it is not a holy writ to be followed without question.

After the brothers recognized that it would not be economically feasible to subdivide and sell their property, an interested potential buyer sought to acquire the entire 40-acre lot to build a nonprofit, private school. The sale would not have involved a property split or a lengthy new water line. It would, however, require the new owner to complete the same quarter-mile road the township raised with the Ervins, as well as expensive sidewalks of questionable necessity.

The private school leadership noted that the costs imposed by the township for “building the roads and sidewalks far exceeded the school’s projected budget.” It chose to consider the property no longer.

Once again, the township’s officious micromanagement effectively rendered Ervin’s property valueless. Insisting that any development on the land include excessively expensive infrastructure improvements that might someday benefit the public means that any potential buyer seeking to develop the property would have to be willing to spend more than its value.

Governments that choose to regulate land use through zoning should be aware that overregulation can quickly lead to community stagnation. Local governments must be careful to avoid overly restrictive rules that effectively prevent a parcel of land from being used or developed for a reasonable purpose. Unfortunately, the Ervins have found themselves in just such a situation in their dealings with Union Charter Township. Even worse, they are not the only ones.

(Editor's note: This article has been updated to add a comment from Union Township. Click here for part 1 of this series and here for part 3.)

|

There’s something wrong with Union Township: Part 2

Township wanted residents to build a road and water line to sell land

Last week, we highlighted problems with the Union Charter Township government, including a pervasive anti-growth attitude toward new developments. One family’s struggle with local leaders illustrates the extent of the township’s overreach.

The brothers William, Richard, Ronald and Robert Ervin own land in the township. These local developers have twice been kept from developing their property by local government. In two separate instances, the township effectively regulated away the value of property the Ervin brothers wanted to sell.

In 2023, the brothers wanted to divide their 40-acre parcel into two parts so they could sell one part to a younger relative. The township, however, refused to grant the requested land division. Employees claimed that the intended development (the construction of a home) was contrary to both the township’s zoning ordinance and its master plan.

Local governments frequently use zoning ordinances and master plans to manage and control development. A zoning ordinance restricts how a property can be used, while a master plan is a long-term guide.

According to the Ervin brothers, the township would grant permission to divide the land, but only if their prospective buyer would build a road, ending with a cul-de-sac, on his property. Township employees also wanted the buyer to build out a public water line, at his expense, that could be tapped if future growth occurred on the remaining, adjacent 30–acre parcel.

According to the prospective buyer, extending the current road and adding the cul-de-sac would have cost approximately $100,000, a steep price for land valued at $60,000. Installing a water line that would serve future development by others would be an additional expense, far greater than the cost of getting a line to his own house.

Union Township officials denied the allegations.

“The Township Administration does not engage in foot-dragging or stifle or stymie land development,” the township told Michigan Capitol Confidential in an email. “The allegation of possible retribution is abhorrent and false. The Township Administration strives to ensure that all who interact with staff are treated with respect and with a focus on a successful outcome for any issue or challenge that needs resolution.”

Township employees also appear to be interested in having the Ervins build a quarter-mile road as part of the larger land division, according to a letter the township sent to William Ervin. The letter cited the township master plan, which included a street to Lincoln Road, a much larger thoroughfare.

The Ervins disagreed with the township’s decision to deny their request to divide the land, and they hired a lawyer to argue their case before the township’s Zoning Board of Appeals. The brothers won their appeal quickly, but they and their buyer chose not to proceed with the sale. Once again, the township was the issue.

The township’s master plan and its requirements made the development of the younger Ervin’s property untenable. Though the brothers won the land division they sought, they had no solution for the township’s demands for extending the public water line or building a road. For this and other reasons, the parties chose not to complete the sale.

Requiring property owners to build infrastructure for future public benefit is not the proper role of government. This is particularly true since a master plan is merely a guide for community development; it is not a holy writ to be followed without question.

After the brothers recognized that it would not be economically feasible to subdivide and sell their property, an interested potential buyer sought to acquire the entire 40-acre lot to build a nonprofit, private school. The sale would not have involved a property split or a lengthy new water line. It would, however, require the new owner to complete the same quarter-mile road the township raised with the Ervins, as well as expensive sidewalks of questionable necessity.

The private school leadership noted that the costs imposed by the township for “building the roads and sidewalks far exceeded the school’s projected budget.” It chose to consider the property no longer.

Once again, the township’s officious micromanagement effectively rendered Ervin’s property valueless. Insisting that any development on the land include excessively expensive infrastructure improvements that might someday benefit the public means that any potential buyer seeking to develop the property would have to be willing to spend more than its value.

Governments that choose to regulate land use through zoning should be aware that overregulation can quickly lead to community stagnation. Local governments must be careful to avoid overly restrictive rules that effectively prevent a parcel of land from being used or developed for a reasonable purpose. Unfortunately, the Ervins have found themselves in just such a situation in their dealings with Union Charter Township. Even worse, they are not the only ones.

(Editor's note: This article has been updated to add a comment from Union Township. Click here for part 1 of this series and here for part 3.)

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

More From CapCon